Introduction

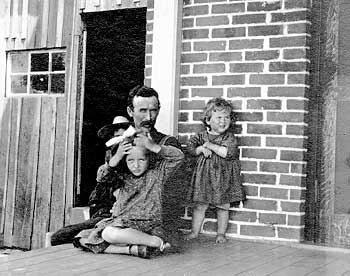

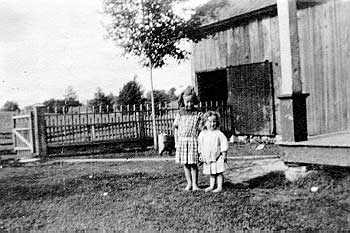

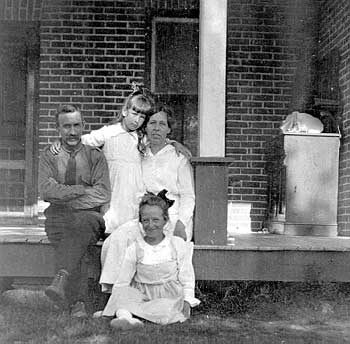

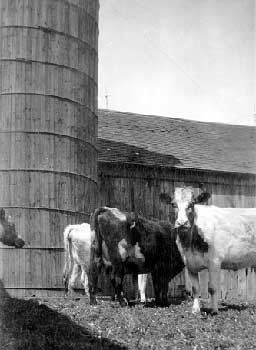

The first of Marjorie Oliver's family to come to Canada was her great-grandfather, William Oliver, who emigrated from Scotland shortly after 1855. What is now the James McLean Oliver Ecological Centre has been in the Oliver's family since 1868 when it was acquired by William Oliver's eldest son George Oliver (Marjorie Oliver's Grandfather). This property was used for mixed farming: hay, grains, vegetables, cattle, sheep, pigs, horses, chickens, and turkeys. They also planted an orchard. James McLean Oliver, his wife Margaret and two children Margaret and Marjorie operated a tourist summer establishment which started in 1906 and continued until 1986. The brick house was built in 1903, and as the tourist operation expanded more buildings were added; two annexes, two sleeping cabins, two house keeping cottages, a sand beach and a cement slip for boats were added to accommodate visiting tourists. Farming and tourism continued for some years until farming gave way to simple pasturing of cattle on both parcels, east and west of Mill Line Road, this lasting until 1989.

Miss Marjorie Oliver has very fond memories of growing up on the shores of Pigeon Lake, particularly of helping her father with the evening chores, tapping trees to make maple syrup, and swimming in Pigeon Lake. Marjorie was schooled at Nogies Creek Public School before attending High School in Lindsay, Ontario. She then went on to Queen's University in Kingston where she obtained her teaching degree and later taught for the majority of her career in Peterborough at Prince of Wales. With this gift to Trent she allows teaching and learning to continue to be a part of the Oliver's legacy.

Memories - by Marjorie Oliver

Oliver Family Pictures

Memories - by Marjorie Oliver

The Clock

I stood for some time looking at the two clock keys as they lay in my hands. One was modern and new; one was frail and old. It was the old one that recalled from the far and misty past those happy, happy years of my childhood.

A clock that has been a part of your household for over a long period of time becomes very much a part of you, and your life becomes regulated by its stead ticking. I am thinking a particular clock that has been in our house for as long as I can remember - actually it has been in three houses. Its first home was a log house built by Grandfather, but the clock outlived him, and it became the property of Father who continued to live there until after he married Mother. The house was cold in the winter; its occupants insisted even the clock would creak and shiver during those long cold nights. Father and Mother decided it was time to build a new house beside the old one on the top of the hill overlooking the lake. On a fine day everything was moved from the old house to the new one and the clock was set on a special shelf in the kitchen. The shelf was well out of the reach of children’s hands and it sat strong and sturdy between two doorways one leading to the cellar and one leading to the dining room. This is where I first became aware of the steady passing of time in minutes and hours. Mother had placed a china swan on each side of the clock. I always felt that it thought they were rather stupid as they seemed to be of no use to anyone, they couldn’t even swim on that shelf. There is a glass door over the face of the clock so that when the light shone through the window at a certain time of day, it was hard to see the hands, and one would either squint or move around until the glare disappeared and time returned.

Photo of the Oliver’s clock as it now sits on the wall of the main house at the James McLean Oliver Ecological Centre. Photo courtesy of Eric Sager.

I have been told that before I was born Mother gave the clock a good cleaning - so good, in fact, that some of the paint on its face was chipped. On that same day Mother pasted a picture she had cut from some magazine on the lower part of the inside of the door; she did not like the inner workings of the clock displayed to all who set foot inside her kitchen. She pasted well; the picture is there to this day. Two ladies, wearing some form of drapery that I could never understand, stood day after day with their backs to the wall and stared out at our household.

The clock was strong; and without rest or break, it continued at tits never-changing pace counting the minutes and striking the hours all day and all night. When I was a child and visited my friends, I was often amazed by clocks that struck hours, half-hours and quarter-hours, and I wished that our clock on the kitchen shelf would do all these things, but Father was not happy when he was surrounded by too much sound. The hours were enough for him; he needed neither halves nor quarters.

Each night as my sister and I lay in bed in our room above the kitchen, we would become award, sooner or later, of the nightly ritual. Father would drag a chair - usually his own arm chair - over to the shelf, climb up, open the door and wind the clock. First came the slow steady muted sound of the winding of the minute hand; in my mind’s eye I could see the z-shaped key held firmly in my father’s hand as he wound up the weight on its fish line mechanism weight being wound on its line. Once the winding was done, we knew that for our family, the day was over. Periodically we would hear a dull clunk in the kitchen and we realized that one of the lines, having grown old and frayed, had finally given up its hold and had let its weight fall. Next day a length would be cut off the reel of fish line and Father would repair the damage.

I think that once in a awhile the feelings of the clock were hurt a bit when Father would go tot he telephone, push the button on the left side of the box, turn the crank on the right side to get the attention of the operator and say, “What is the correct time please?” I used to imagine that the face of the clock reflected its embarrassment as it tried to hide behind its hands.

Father and Mother grew old and to escape the cold of winter and the certainty of being snowed-in, built a house in the village and moved there. For some reason the clock was left at the farm house. Father never felt that he had left his old home, for every spring there was the going-home day. He would stand for a time on the hill overlooking the lake to see that all was well with his property; then he went inside to wind his clock which always responded to his touch. When Father died, the clock missed his gentle hands, and it would not be comforted by anyone else’s; it just stood still.

A fixer of clocks attempted to set it straight and explained as he handed me the two keys that the thread of the old one had worn and that the new one would “do the trick”. It worked for a while, but I think the clock is frail and it misses the old days as I miss the nights when Father climbed onto his chair to wind up both weights of his clock so that he could hear it strike while he was dreaming of the good days when he alone was responsible for all things at the farms, and when he and Mother and his children regulated their lives by its steady ticking.

One fall day when i was closing up the farm house in preparation for winter, I realized how lonely I had become for the members of my family who, one by one, had left this land for a “better one”, and my eyes fell on the face of the silent clock. I took it from its shelf and carried it in my arms to the waiting car. The chipped face, the faded picture, the heavy weights, and the twisted key brought back to mind those simple days when our household was made bright by the steady ticking and striking of Grandfather’s clock. It now sits in a special corner in the house in the village just as old folks used to do when they no longer trusted themselves to do their daily tasks.

Chores

Our house and barns stood on a hill overlooking a lake. And right now I am remembering the winters of my childhood - their tasks as well as their joys around our stables.

Each night Father would put on his heavy rubbers, extra sweater, sturdy smock, woollen and leather mitts; light his lantern, and stand for a minute while I made up my mind whether to accompany him or not - usually I would bundle up and go with him to “bed down the animals”. As we made our way to the stable, I walked behind Father who carried the lantern. The shadows of our feet stepped high, our breath rose steadily in two puffy spirals, and the crunch of the snow sounded frostily under our boots. We entered the stable first. It was warm with the contented breathing of the cattle and horses. We began the chores by bedding the horses. Father always told me to hold the lantern so that I could see, and then he, too, would be able to see what he was doing. Soiled straw was forked from the floors of each stall, and fresh straw which was to form a bedding, was scattered in its place. Hay from the passageway was forked into the mangers. The cows, the young cattle, and the calves were similarly attended to, and as we left the stable there was the pleasant sound of steady chomping.

We next looked after the sheep. My father’s ancestors had been shepherds in Scotland and he had a special love for his sheep and lambs. As we opened the door of the pen, their eyes blinked as they looked toward Father who would raise his lantern to see that all was well with his flock. They welcomed the feed we gave them and munched daintily as we left them and proceed on to the pig pen. Here we were greeted by inquiring grunts which soon changed to heart-warming slurps to great satisfaction as they hastily finished the chop and slops. The door was carefully shut and we made our way out through the sheep pen where the sheep sleepily watched us depart into the cold of the night air. The windows of the kitchen shone out their welcoming warmth as we made our way back, and our mouths watered at the thoughts of toasted buns and hot tea that Mother had waiting for us. Father would say, “It’s going to be a cold one, but the animals are all warn and fed.” And with that remark he threw his mitts under the stove to dry out for the morning. He sat down beside the wood box, picked up a piece of cedar and with his draw blade made shavings which would help to start the fire in the stove next morning. He then settled himself in his arm chair beside the lamp at the end of the kitchen table to sip his tea and read his “Globe” while Mother made the rolled-oat porridge which would be heated for our breakfast in the morning. The kitchen at night was a warm and happy place full of comfort and serenity.

Winter mornings were a different matter. Milking was done and the warm milk was carried steaming to the kitchen where it was separated into cream for us and skim for the pigs. Washing the separator was a tedious chore and I was always glad when I could escape. Bowls, spouts and dishes had to be washed, rinsed and re-assembled. Huge bowls of hot porridge, thick slices of home-made bread toasted over the hot coals of a wood fire, eggs and home-cured pork prepared us well for the work of the day. If for some reason I did not go to school, or it were a weekend morning, I had my role to play and usually the barns, stables, and pens made up the scene in which I had my part.

Water holes had to be cut before the animals were let out of the stables. Every morning Father dressed for the outdoors with the ear lugs of his cap pulled well down and his mackinaw coat collar turned well up, picked up his axe and followed the path to the lake. There he chopped the water holes clear of ice. Back up the hill he would go, replace the axe and head for the stable to be welcomed by the rattling of the chains against the stanchions, and we knew the cattle were anxious to get at that cold lake water. One by one they were let out, but usually they trailed one another slowly and ploddingly. Next came the calves that in their childish way kicked up their heels and even slipped in their hurry to get out. The young cattle - the year olds - followed eagerly but more surely. As they all got out, they sniffed the air, filled their lungs, and filed their way to the lake. The horses left the stable last and they were the most frisky of the lot; they galloped around the yard, and often before going to the lake would lie on the snow and roll from side to side, get up, snort, and streak for the water holes. Sometimes I went to the sheep pen, opened the door and hid behind it until the sheep and especially the ram had left. The sheep did not seem to be drawn to the lake as did the other animals. In the meantime, on a fair day, Father would scatter hay in the barn yard, and then all the animals came back from the lake feed was ready for them. The hens picked their way gingerly over the snow to pick up the few that had shaken from the feed put out for the animals. On such days the roosters appeared less cocky than usual as their attention was absorbed by avoiding icy patches and by snapping up especially large morsels. It was usually Mother who cooked some sort of mash as a warm treat for the grateful hens and chickens on a particularly cold day. The cackling discussion of the goodies found in the mash was a rewarding sound that reflected complete satisfaction of the hen house.

Once in a while the whole barnyard would be in an uproar. After a heavy snowstorm, the roof of the barn would become loaded with snow, but when a sunny day came along and the roof warmed up a bit, the whole mass of snow would slide off with the thunderous upheaval of a small avalanche, and all the animals would gallop away and then turn and stare at what had scared them.

The cleaning of the stables came next. Shovels cleaned the floor of the stalls into the gutters down which ran the liquid to some underground passage outside. Father then came and shovelled the solid mess into the wheelbarrow which he wheeled outside to the manure pile. Back-breaking trips had to be made to get the smelly but rich and pungent stuff outside where it froze solid during the winter. In the spring when it thawed out, there came the disgusting work of “drawing out manure” to the fields where it was used as fertilizer.

By this time the stable was well aired and we went up to the barn to “throw down” hay and straw from their lofts. A slide door was pulled open, hay was forked onto the floor, then it was pushed along in one grand pile to the door and shoved through to the stable beneath. Straw was forked from another loft and through another door to be used later for bedding. We next went into the old barn that Grandfather had built, and we forked hay down the chute into the sheep pen. Back to the stable we would go to do what I liked best. A turnip bin had been filled in the fall with hundreds of turnips which were great for pitching. I pierced one with a pitch fork and hurled it down the length of the cows’ mangers. Thirteen cows- thirteen turnips. They were then picked up one by one and tossed into a manger as a treat for each cow. Calves and year-olds could not manage whole ones, so turnips were thrown into the pulper and chopped into slices and carried by a shovel to these young animals. The thing I liked about this task was the tasty nibble of the crisp centre of the turnip; the thing I did not like about the task was lifting the roots in my mittened hands and seeing the red wool become grey and damp. While I did this Father stood on a box, reached up and pulled back a little paddle-like wooden slide at the end of a chute along the ceiling, and down would come a stream of golden oats from the granary in the barn above and into a bucket held up high by Father. The oats were special and were divided among the boxes beside the horses’ mangers.

Late in the afternoon came the task of carrying boxes of corn ensilage from the basement of the silo to the mangers of the cows. The stuff smelled of fermented corn and my nose wrinkled in an effort to avoid the stench. The ensilage was also very heavy. I could fill the boxes, but I could not lift nor carry them; this work was left to Father or Mother who often helped him with the chores. The cows always seemed to find the feed most acceptable.

If the weather were good, the stock stayed out in the sunshine and good air-being very serious and staid for the most part, but getting on with the business of eating of just standing there thinking, no doubt of the treats awaiting them in the stables. At times they became skittish and playful and kicked up their heels; but in a matter of seconds the older animals settled down as if aghast at their unseemly conduct. If the weather were cold and stormy, the cattle made for the open doors, and unerringly took the same stalls day after day, and with great relish gulped down the cool crisp turnips. The horses, on the other hand, nosed in their oat boxes and mangers for carrots, oats and hay.

At least once in a winter on a very cold night, Ginny, the good and faithful horse that pulled us in buggy or cutter over miles of roads and miles of ice on the lake, would become possessed with an idea of staying outside for the night and would kick in defiance of being coaxed in. At regular intervals Father would put on all of his outer winter clothes, light his lantern, go to the stable, shake a pan of oats, and call to the mare that would toss her head and go galloping around the barns. Father worried about her being out in the bitter cold and would go out in the middle of the night to try to tempt her again and finally she would give in, and we would all settle down for the rest of the night knowing that Ginny had a last found her senses and had gone into the warmth of the stable.

The comradeship between Father and me was sweet indeed. He realized there was “ a time to keep silence and a time to speak” In his Scottish blood it was not natural to reveal the soul too nakedly, and although he said little, I knew him well enough to sense his pride and pleasure when I accompanied him to do his many chores - especially those done at night. The cold quiet of a bright moon-lit winter night, when the sky was heavy with stars, seemed to tighten the bond between us and our souls felt at peace. We understood each other.

Farming

Of all the animals on Father’s farm, the sheep were the most gentle and the most passive; and I am sure he loved them the best. When he fed them in the pen during the winter months, they looked up to him in trustful anticipation for the food so generously and lovingly given to them.

It was at lambing time that he was most anxious for his sheep. As I look back,

It was at lambing time that he was most anxious for his sheep. As I look back,

it seems strange to me that I never saw an animal give birth to its young. I saw the tags on the cows’ stalls as a reminder when they would “come in” to motherhood. I was always aware of the pen being cleaned and made ready for the birth of a colt or calf. I realized that Father made frequent trips to the pig pen when a sow was about to farrow, but it was the sheep that caused him the most concern when they were about to have their lambs. The lambing season was in the spring; if the days and nights were warm, the sheep were safe right in the meadow; if on the other hand, the night suddenly became cold and snow fell, new born lambs were in trouble. It was on such a night that Father and Mother would dress, light the lantern, call the dog, and make their way to the meadow to guide the flock up the lane to the warm dry pen. Father often had one or two lambs in his arms or tucked in the shelter of his smock. One event stands out vividly. On a late afternoon-one of those cold damp days in spring-Father came up the lane; he carried in his arms a very young lamb; beside him walked the mother with her head raised in concern as she watched her baby cradled in human hands; on the other side walked the faithful dog. When we went to church the next Sunday the stained glass window behind the choir suddenly took on new meaning. There was the Christ with a staff in one hand, a lamb in the other hand and a sheep looking up anxiously toward her offspring. On that Sunday of my childhood, Christ and Father were the same.

Ring, the dog, was part of our childhood. Where ever we walked, he walked, except to school. On our return from school in the afternoon he always met us at the woods gate where the cows were waiting to be brought in to be milked. He was not a house dog - he was a stable dog, and there he spent his nights. Ring was afraid of one thing - thunder storms. When one came up, he crawled under the house or veranda and stayed there till it was over. Ring loved to swim. We would throw a stick out into the lake and he would paddle after it, take it in his mouth and bring it to shore to lay it down at our feet, shake the water from his coat, and wait for us to throw it out again. The birds had fun with Ring; they would tease him by flying low over the beach and out over the lake; he would chase them over the shore yapping and barking half in fun and half in earnest; when they headed for their flight over the lake, he was not to be daunted, but swam still barking joyously until, when they were well out of reach and sight, he turned back to the shore proud that he had driven them away and shook water all over us as much as to say that he also shook the birds out of his mind.

Ring, the dog, was part of our childhood. Where ever we walked, he walked, except to school. On our return from school in the afternoon he always met us at the woods gate where the cows were waiting to be brought in to be milked. He was not a house dog - he was a stable dog, and there he spent his nights. Ring was afraid of one thing - thunder storms. When one came up, he crawled under the house or veranda and stayed there till it was over. Ring loved to swim. We would throw a stick out into the lake and he would paddle after it, take it in his mouth and bring it to shore to lay it down at our feet, shake the water from his coat, and wait for us to throw it out again. The birds had fun with Ring; they would tease him by flying low over the beach and out over the lake; he would chase them over the shore yapping and barking half in fun and half in earnest; when they headed for their flight over the lake, he was not to be daunted, but swam still barking joyously until, when they were well out of reach and sight, he turned back to the shore proud that he had driven them away and shook water all over us as much as to say that he also shook the birds out of his mind.

Ring had other troubles besides birds. During the warm weather he would have two or three meetings with a skunk. How the smell clung to him; and how we tried to avoid him, but he kept slinking up to us and looking us in the eye as much as to say, “You stink, too!” I felt most sorry for him when he came whimpering home after a one-sided combat with a porcupine. He had learned during his puppy-dog days that Father was the only one capable of helping him, and he would make straight for him with his nose raised. “Please, Sir, I have done it again.” Father took his pincers and plucked the quills from his head. Then Ring would open his mouth because, as he could not resist the urge to bit his quarry, he always came home with a mouthful of quills; he kept his jaws open just like a patient in a dentist’s chair until Father had gotten every quill. Ring was sensitive and loyal. My sister tells me that when I was very ill, the doctor was called in the night from Lindsay twenty six miles away. Mother feared sickness and needed the strength of the lady who lived on the next farm but she had no telephone. It was decided that my sister would go for the neighbour whom we called Mrs. Will. Poor Margaret! She told me about her midnight journey long after we had grown up. Mother helped her to dress, Father lit a lantern, and a little girl set out alone in the dark to get help half a mile away for a sister the family thought was dying. She considered crossing the fields, but in the dark she feared the cattle pastured there and that she might lose her way. “Poor Lucy Grey!” She called, “Here, Ring”; and he gladly came. “Here am I. Lean on me and we’ll make it”. She walked beside him with one hand on his head, and the other hand clutching the lantern. Down the lane they went, opened the gate and made their way up the road past the woods gate and up the cherry -tree hill. They peered their way with their eyes, and picked the road with their feet. She held the lantern high so that she would not miss the neighbour’s gate. She spied it, opened it, closed it again as she had been taught so that the cattle would not sander out or in, and with Ring still at her side went down the long lane and hill to the house where she had to rap and rap to make herself heard. When the neighbour who knew all about illness and little girls, opened the door, Margaret fell weeping into her arms and sobbed out her story while Ring pushed against them both to show his sympathy and concern. The return trip was easier for Margaret because she had Mrs. Will as well as Ring.

Ring grew old and we got another dog-a bitch- named of all things Buster - who regularly produced a litter of puppies. We also had new neighbours who had many children and a dog. One summer day the sheep were being run by dogs. Father took up his rifle, hurried to the woods and saw to his dismay that one sheep had been killed by a dog that was worrying another. One bullet was all that was needed; the dog was dead and the neighbour’s children were heartbroken. In the settlement afterwards, Father offered the children their choice of Buster’s latest litter and they, at least, were happy.

The sad, sad days of my childhood were those when animals were sold. The poor little lambs were loaded and taken to the station to be shipped out on the cattle cars. The same fate awaited the calves and pigs. I do not remember Father killing any animal except a pig each fall to give us pork for the winter. That slaughter day was a day of terror; knives were sharpened on the grindstone for the killing and for scraping the hairs from the skin; a boiler of water was heated to the boiling point because scalding water made the scraping easier. I covered my ears and ran to the farthest corner of the house so that I could not hear the squeals of the unfortunate porker. The horror was all forgotten when we dined on headcheese Mother had made. The process of making that took all day. The head was boiled, skinned, boned and its choice pieces cut up into small bits which were set to jell in the juice of the boilings. In order to have the headcheese firm it was put into an enamel pan, a pie plate was pressed down on it and a flat iron was placed on top to hold the plate from popping up. The rest of the meat was salted. Mother would slice pieces to be fried, but she always parboiled it first to remove the salt. Fried pork, potatoes, and baked beans made a good winter’s dinner.

The sad, sad days of my childhood were those when animals were sold. The poor little lambs were loaded and taken to the station to be shipped out on the cattle cars. The same fate awaited the calves and pigs. I do not remember Father killing any animal except a pig each fall to give us pork for the winter. That slaughter day was a day of terror; knives were sharpened on the grindstone for the killing and for scraping the hairs from the skin; a boiler of water was heated to the boiling point because scalding water made the scraping easier. I covered my ears and ran to the farthest corner of the house so that I could not hear the squeals of the unfortunate porker. The horror was all forgotten when we dined on headcheese Mother had made. The process of making that took all day. The head was boiled, skinned, boned and its choice pieces cut up into small bits which were set to jell in the juice of the boilings. In order to have the headcheese firm it was put into an enamel pan, a pie plate was pressed down on it and a flat iron was placed on top to hold the plate from popping up. The rest of the meat was salted. Mother would slice pieces to be fried, but she always parboiled it first to remove the salt. Fried pork, potatoes, and baked beans made a good winter’s dinner.

I feared the horses, but somehow I loved them for they remained even though other animals were sold, and the horses represented a permanent fixture. One night a great commotion was heard coming from the stable. Father went down to find that one of the horses had broken its halter and was loose letting its hoofs fly at the flanks of the helpless Ginny, who having been tied securely in her stall, could not defend herself. The attacker was quickly put in his place and poor Ginny’s wounds were inspected. In the morning the veterinarian came from the village to treat her cuts. They had to tie up her feet in some way so that she could not kick anyone during the treatment. Up in the kitchen - far away from the agony - Mother kept saying, “Poor helpless brute!” While I was away at college, I kept in touch with all the events at home by telephone. Sad new came late one night when I was told that Ginny, having grown old and sick, had to be “done away with”. They led her out of the stable, where she had always felt safe and secure, and into the yard where a neighbour shot her. “Poor helpless brute!” Father had not the heart to kill her. I came away from the telephone and cried my heart out in the memory of the days when Ginny and I grew up together.

Father kept two brood mares, Skip and Maud, and periodically they had colts which grew up and were sold, but Skip and Maud stayed on. Margaret and I drove to the village with Ginny and the cutter to get mail and groceries. On our way home we met another cutter and a horse being led behind. As we got opposite the oncoming rig, Ginny and we recognized the horse at once. We stood up in the cutter and all we could say was, “Oh Skip!” “Poor helpless brute” had been sold and we were heart broken in our misery over our fear for her fate; would the owners be kind?

The hen house and hen yard were always alive with industry. The head rooster busied himself with his harem, with crowing his triumphs, with scratching for food and with fighting any nervy young cockerals. The hens were kept busy laying eggs, mothering their chicks, and scratching for food. Their house was a smelly place - straw on the cement floor, a row of windows and screen facing the south, two rows of nests and several polls for roosts. I liked the door. It had a wee opening at the bottom with a slide door which was opened every morning. All the occupants could hop in or out as they pleased - the hens to lay their eggs in the nests, and the roosters to do their strutting. It was a friendly place.

The hen house and hen yard were always alive with industry. The head rooster busied himself with his harem, with crowing his triumphs, with scratching for food and with fighting any nervy young cockerals. The hens were kept busy laying eggs, mothering their chicks, and scratching for food. Their house was a smelly place - straw on the cement floor, a row of windows and screen facing the south, two rows of nests and several polls for roosts. I liked the door. It had a wee opening at the bottom with a slide door which was opened every morning. All the occupants could hop in or out as they pleased - the hens to lay their eggs in the nests, and the roosters to do their strutting. It was a friendly place.

During the winter days our hens did not lay eggs, and for a period of two months or so we did no egg gathering. But early in the spring life flooded back and the odd egg was laid; we had to make several visits to the hen house to pick up the precious bits to save them from freezing. Mother kept them until she had enough - one for each of the family - and what a treat those fresh eggs were for supper. She usually boiled them and we would often break them over good fried potatoes. Some of the hens would “lay away” in the spring and then there was the joyous adventure of scrambling over the hay lofts to search for their hideouts. Mother sensed that they were getting ready to “set”. A dozen eggs were marked with a pencil - usually a blue one- and placed under the hen in her chosen nest. Once a day Mother would check all the eggs in the nest and if there were an unmarked one, she knew it had been freshly laid and she would take it out of the nest. The marked ones were left for the full “setting” time. As soon as the chicks were hatched, they with their mother were put into coops in the back yard near the house. I felt sorry for the poor hen cooped up there day and night, but I was advised that she would wander away and ear knows what might have happened to her brood. A pan of water was placed under the lowest slat of the coop so that half of it was in the coop and half of it was outside; the pan had to be filled with fresh water several times a day; it was hot in that back yard when the sun poured down. I loved the feel of the chick’s head pressing against my hand when I cuddled it in my small fingers. In the afternoon the whole brood would crawl into the coop to snuggle under the wings of the mother hen. Once in a while a skunk, hungry for chicken, would dig under the coop in an attempt to rob the whole family. Then such a squawking would drift upstairs to our bedrooms. Father would pull on his pants, go downstairs, pick up his rifle, and go peering out into the night were the white streak of the skunk proved to be a god target. If he missed the stink soon pervaded the whole house. Next morning he would set a skunk trap. A hole of about two feet was dug; a barrel with a piece of bacon on the bottom was balance on the edge of the hole; when the skunk sniffed the bacon, he ventured into the barrel which immediately tipped with his weight to the bottom of the hole and the skunk was trapped, but rarely did he set off that horrible stink. In the morning Father and the hired hand carefully lifted the barrel with a pole which had been thrust through the top of the barrel and carried it to the field where they let the animal out and shot it. The chickens were safe; but the trap was baited again just in case another robber appeared on the scene.

I shall always remember the wild things that were a part of my childhood on the farm - the bobolink that lived in the orchard; the wren that nested in the fence post; the drown thrush that lived in the lane; the swallows that built rows of mud nests under the eaves of the barns; the phoebes that balanced on the fence wires to sing their songs; the orioles that wove their nests in the maple trees; the sandpiper that teetered along the beach; the goldfinch that darted among the bushes; the humming bird that seemed only a handful of vibrating energy; the robin and bluebird whose arrival spelled spring; the hawk that occasionally helped himself to a chicken; the heron that seemed all legs; the Canada goose that honked its way north in the spring and south in the fall; the whip-poor-will what never gave up; the loon that laughed and mourned out on the lake; the groundhogs that were threatened by the dogs; the foxes that seldom dared to come near the barns; and the squirrels and chipmunks that were kept under control by the cats.

Early in the spring we were taken for a walk along the shore to see the lunge that came into the shallows to spawn. We had to be both motionless and quiet so that the fish would feel safe from any danger as they were drawn by that urge to seek a suitable place for the business at hand. At last we could see the large beautiful shapes swimming along the protection of a sunken log and there carry out the purpose for whence they were sent. In no time it was all over. Their graceful easy movements filled me with wonder and I slipped my hand into that of the person standing beside me. The handclasp was a sign that we had shared in a very glorious spectacle. On the way back we picked some of the “lilies of the field” which Mother loved. Ever since, I seem to connect in my mind those pure white lilies with those graceful sinewy fish. Such sights and outing all added happy moments to our young days.

Those happy days of childhood made beautiful by the close companionship of parents and animals will ever remain in my memory; now and then I close my eyes and find myself at home surrounded by all those animate things of my youth that I hold so dear to my heart.

The Lake

The lake has always shared in many of the events in the life of our family. Even our conversation could not get along without it. “Someone had gone down the lake; he had gone to the lake; he went up the lake; he crossed the lake; he swam the lake; the lake took him.” Day after day we were aware of its many and different moods because it was ever in sight of our home. Between the house and it lay a rolling lawn, an orchard, a watering place for the animals, and a sand beach for us. In the summer we could sit on the veranda and hear the water slapping on the shore and the loons laughing hysterically or crying mournfully some where on the lake. Mother told us that when the loons laughed we would certainly have windy weather, and when they mourned we would certainly have rain in a day or so. In the fall and spring we could hear the honking of the geese and we would watch them skiening across the sky and over the lake to disappear behind the roofs. We would run around the house to keep them in sight as long as possible for they were always a source of wonder, announcing that spring was here, or that fall was on its way. In the winter we could hear a fierce wind blowing across the lake bringing with it snow and sleet that battered against the windows while we remained warm and secure within the solid walls of our house. Stiff and cold beauty was ours for merely looking at the ice-bound lake on a clear moon-lit night when God seemed close to our world indeed; it was ours also on a clear frosty morning when the sun caused the whole scene to glitter with tiny sparkling fires.

Storms came up suddenly on our lake and often we would watch a wall of

Storms came up suddenly on our lake and often we would watch a wall of

rain advance steadily and sometimes swiftly from the far shore to ours. Thunder storms were one of my worst fears when I was a child, and at the first faint distant rumble I would run crying to the house to be comforted in my mother’s arms. Father used to tell of paddling three miles to the village to buy a sack of seed corn which he placed in the bow of the canoe. As he emerged from the shelter of the wooded river shore into the open lake, a storm came up, and with each swell the corn in the sack shifted, and it was only with the utmost dexterity mixed with a certain amount of luck that he managed to reach the safety of the beach.

We felt that we had conquered the lake when Father bought his first and only launch with an inboard engine and seating room for twelve people. The motor was at the stern of the boat and the steering wheel was at the bow, but by pulling on a rope which was run through rings all around the inside of the hull Father could drive his boat all by himself no matter where he sat. The first day I was allowed to steer - I had begged for some time - I could not keep on a straight course, but swung too hard to the right, and then in an effort to correct my error swung too far to the left. I gave up the helm in a scene of frustrating tears.

Sheep-washing day arrived when the lake water had lost its spring chill.

Sheep-washing day arrived when the lake water had lost its spring chill.

Some sort of rail corral was built out into the water, and one by one the sheep were drawn into it. Father and a hired hand, having put on old overalls, would wade into the water, grab a sheep, give it a good scrubbing and then take it to the barn so that it would not get its wool soiled again. By the end of the day the whole flock would have been washed and in the barn for the night. The next day a table built especially for the purpose of shearing sheep was set up in the barn yard. A sheep was brought from the barn, placed on the able and held by the hired hand while Father carefully and quickly, but with seldom a nick or slip, sheared the fleece from the helpless sheep which, at last, was set free to look for its lamb, that by its bleating told the whole barn yard that it did not recognize its denuded mother. There was much merriment in our house-hold over an advertisement in the local newspaper announcing that a certain farmer was “in a position to shear sheep.”

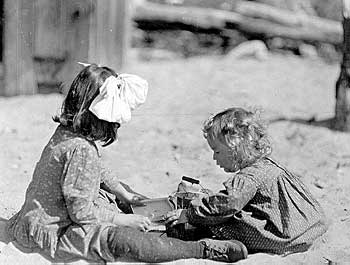

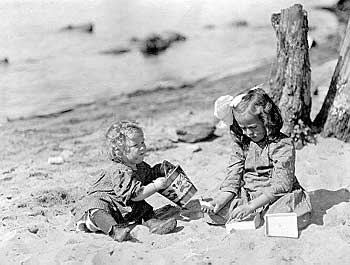

The sand beach that stretches along our shore was our favourite play

The sand beach that stretches along our shore was our favourite play

ground for the summer. My sister and I spent day after day there dressed in our long-sleeved print dresses, stockings, and boots. Our toys were pails, shovels, and small tin dishes. We dug canals, built castles of sorts, and made sand cakes set in our tiny moulds. It was bun to dig channels from the lake and watch the water licking our shovels as it followed them; but I always felt a bit sorry for the water then we plugged up the channel and it had to turn back to the lake. I well remember having a hole in the toe of my boot and poking my finger into it in a fruitless effort to pull out the sand. Sometimes we would take off our shoes and stockings, hold up our dresses and petticoats and wade in the shallow water. If the water were chilly, we shivered and tingled in the anticipation of daring to wade out a little farther until, to our sorrow, our dresses and petticoats trailed and were wet in no time. There was always the unpleasant task of pulling stocking over wet legs because we never took towels to the lake - we were there only to play on the beach.

When Mother and Father were on the scene we could swim; I cannot remember learning to swim, but I do remember the constant caution that we must swim in a path parallel to the shore, and never swim out into the lake until we were in “over our heads”. We went swimming early in the spring. It was only in later years that my sister told me how she feared those first swimming days because she was possessed by the thought that she might - just might- touch the drowned body of some unfortunate person who could have broken through the ice during the winter. I always dreaded putting my feet down and feeling weeds swirling and clinging to my legs. I quickly pulled them up, tried to keep head and feet well above the water and struck off for another area. Now that I have grown old and do not swim anymore, I dream at night of swimming through weeds and sunken trees that lined one shore of the river that passed through the village some three miles distant from our home.

In the autumn the lake changed with each new day. On one morning it would appear as an innocent expanse of still beautiful water under a clear blue sky and would reflect on its surface the crimson and golden forests. On the following morning it could be difficult to see the lake over which hovered a dense fog that our eyes could not penetrate no matter how hard we peered. Father had a good sense of direction and through the dripping air could navigate his boat anywhere on the lake. But when the sun broke through, the lake regained such a look of innocence it seemed to suggest that there had not been any fog at all to trouble us, and that we must have imagined the whole affair.

As winter drew near and the temperature went down, a coating of ice would form each night near the shore, but by noon it would have melted in the sun or have crushed in the wind. But sooner or later it remained all day and for each day thereafter it would extend farther and farther out until the whole lake was frozen from shore to shore. It was then when we skated - the whole family - Father, Mother Sister and I. The dog, Ring, was wild with joyful excitement in being included in our fun. The winter words of caution echoed those of summer, “Skate along the shore, not out towards the river.” When Father know the ice was thick enough, we travelled by horse and cutter across the lake to the village. But before any such trip the horses had to be “sharpened”; they were taken to the village blacksmith, who had a dark cavern of a shop beside the river, to have the corks on their shoes sharpened so that they could have a sure grip on the ice. Travel on the lake could be dangerous - especially for those who did not know the currents, but Father knew all of the dangers and we always had faith in his judgment. “Wonderful Father”. When we would return from the village, Father always stopped at the water hole near the shore, chopped it clear of ice to give the horse a drink, and then with no urging she would make a grand dash up the hill to the barn. On a very cold night in the early winter we would hear a roar and a growl from the lake and some one would be sure to say, “The ice is making tonight.” Once in a while there could be heard a sort of thunderous crack and the next day could be seen a “bust” - a place where the ice had heaved from one shore to the other in a mighty crack. Drivers and their horses had to be very cautious when crossing one of these “bursts”,; sometimes the ice which had heaved up and had no water under it would crack when the weight of horses and sleighs forced it down.

When the ice was well over a foot thick, it was time to fill the ice houses.

When the ice was well over a foot thick, it was time to fill the ice houses.

Sometimes farmers exchanged work and helped one another. One precious neighbour often left the work of filling his ice house until late in the season; as some one said, “Nate always leaves his ice harvesting until spring break-up when he has to catch the pieces floating by with a pike pole.” Lines were strung about twelve or fourteen inches apart; a sawyer, guided by the lines would cut long strips which in turn were cut into twelve or fourteen-inch blocks. These blocks were fished out of the water hole with a pike pole and ice tongs and slid up a plank onto a sleigh. The blocks were heavy and no one ever over-loaded the sleighs which were then drawn to the ice house. Again the blocks were slid down the plank and some one inside the ice house clasped them with his tongs and placed them in position on a layer of sawdust. I used to marvel at the beautiful blue coldness of the blocks, and it was only when I touched them did I realize that under that beauty was a cruel heart indeed. They were never allowed to touch the walls of the ice house because sawdust had to be shovelled all around the ice and on top to form an insulation against the heat of summer. If the summer heat wasn’t too much, ice could last in the ice house through till August. In order to caution travellers on the lake that ice cutting was in progress, cedar branches were cut and placed around the hole. Cold days were the best for ice cutting because the men would not become soaked with melted particles of snow and ice.

I used to watch the rigs travelling on the ice, and in those days there were many. If Father and Mother went to town, we could see them coming home from near the mouth of the river toward the house and as they neared the shore, the horses trotted faster at the thought of a full manger. I have watched sleighs go down the lake on a windy winter day; the figures of the men hunched against the storm; the heads of the horses lowered as they plodded steadily on scattering the snow in all directions; their mane and tails flying.

On each Friday winter night Father met the eight o’clock train which brought my sister and me from the town where we attended high school. He never failed to be on the station platform waiting or us to scramble down the steps of the train. He was well wrapped up against the cold- a fur hat pulled down over his ears; a fur coat over woolen shirt, sweater, coat and coarse woollen pants and heavy woolen underwear; two pairs of woolen socks knitted by Mother, boots, overshoes, woolen mitts, and leather mitts. Father seldom if ever spoke of his love for us, but on those nights as he laid the loving grasp on our arms, he cast an anxious look into our eyes to see if all was well with us. Together we walked down the street to a driving shed where the horse and cutter had been tied because Ginny had a great fear of trains. Father was always particular about the way we got into the cutter. Groceries, mail, and our grips were placed under the seat. Snow had to be kicked or knocked off our boots so that it would not melt on the floor of the cutter. Your stood up in the cutter with a corner of the buffalo robe in one hand; you would then wrap it around you; the person beside you would do the same with the opposite hand; both of you would sit down at the same time. If you did this properly, the wind would not get in under the robe. I usually sat in the middle and would hide behind Father’s shoulder when a bitter wind blew. In spite of the robe and the closeness in the cutter, your feet could feel like blocks of ice; it was then that Father would suggest that you get out of the cutter and run for a while to get your blood circulation again.

On each Friday winter night Father met the eight o’clock train which brought my sister and me from the town where we attended high school. He never failed to be on the station platform waiting or us to scramble down the steps of the train. He was well wrapped up against the cold- a fur hat pulled down over his ears; a fur coat over woolen shirt, sweater, coat and coarse woollen pants and heavy woolen underwear; two pairs of woolen socks knitted by Mother, boots, overshoes, woolen mitts, and leather mitts. Father seldom if ever spoke of his love for us, but on those nights as he laid the loving grasp on our arms, he cast an anxious look into our eyes to see if all was well with us. Together we walked down the street to a driving shed where the horse and cutter had been tied because Ginny had a great fear of trains. Father was always particular about the way we got into the cutter. Groceries, mail, and our grips were placed under the seat. Snow had to be kicked or knocked off our boots so that it would not melt on the floor of the cutter. Your stood up in the cutter with a corner of the buffalo robe in one hand; you would then wrap it around you; the person beside you would do the same with the opposite hand; both of you would sit down at the same time. If you did this properly, the wind would not get in under the robe. I usually sat in the middle and would hide behind Father’s shoulder when a bitter wind blew. In spite of the robe and the closeness in the cutter, your feet could feel like blocks of ice; it was then that Father would suggest that you get out of the cutter and run for a while to get your blood circulation again.

Those Friday nights on the lake will always be remembered as happy interludes of close and deep family companionship. We told Father all about our successes, our failures, and our anxieties over our lessons; he told us of the happenings at the farm and of how he and “Mom” were faring during the winter storms; how the stove pipes had been on fire one morning; how the hens had started to lay again; and how “Mom” had made a big batch of bread that morning. Moon-lit nights were of exquisite beauty; stormy nights were “talkless” nights when we strained our eyes to keep a watch on the horse to see that she would not stray off the track and wander out toward the river. No matter what the weather, as soon as we were beyond the shelter of the trees along the north shore of the river and were out on the great expanse of the lake, we looked for the light shining from our house. Without fail Mother saw that the part of the house facing the lake was lit so that we would be guided safely home. On a clear night we could see the smoke from the kitchen chimney and from the furnace chimney, and we remembered the Scottish prayer, “Lang may your lum reek” (Long may your chimney smoke). Such loving care and such anxiety for our comfort and safety against the numbing cold of those winter nights on the lake made our hearts warm and our souls bright.

Those Friday nights on the lake will always be remembered as happy interludes of close and deep family companionship. We told Father all about our successes, our failures, and our anxieties over our lessons; he told us of the happenings at the farm and of how he and “Mom” were faring during the winter storms; how the stove pipes had been on fire one morning; how the hens had started to lay again; and how “Mom” had made a big batch of bread that morning. Moon-lit nights were of exquisite beauty; stormy nights were “talkless” nights when we strained our eyes to keep a watch on the horse to see that she would not stray off the track and wander out toward the river. No matter what the weather, as soon as we were beyond the shelter of the trees along the north shore of the river and were out on the great expanse of the lake, we looked for the light shining from our house. Without fail Mother saw that the part of the house facing the lake was lit so that we would be guided safely home. On a clear night we could see the smoke from the kitchen chimney and from the furnace chimney, and we remembered the Scottish prayer, “Lang may your lum reek” (Long may your chimney smoke). Such loving care and such anxiety for our comfort and safety against the numbing cold of those winter nights on the lake made our hearts warm and our souls bright.

It was the law of the land that during winter months, when one could not hear sleighs and cutters sliding over the snow-packed roads, each horse should have a strap of bells around its body or bells should be put on the shafts of the cutter. Father did not like noise, but he stayed within the limit of the law by having one bell on the shaft of his cutter. When, with the curiosity of childhood, I asked him why he did not have more bells to make a merry sound on those quiet winter trips, he replied that when he was alone in the cutter he liked to think and that the jingling of the bells interrupted his thinking - good Scottish reasoning.

When we drove up to the kitchen door, Mother was standing there with a lit lantern which was taken from her and set on the snow near the cutter. We gathered all that had been stowed under the seat, helped Father out of his heavy coat and made our way with our loads through the shed and into the warm kitchen, while Father unhitched the horse and made his way to the stable. After he had attended to the needs of the horse and had put the cutter into the driving shed he, too, came stomping the snow off his overshoes to join his family in the kitchen. I can feel Mothers’s warm hands undoing our scarves and coats while we shivered and shook helplessly and blinked at the light. The fire in the wood stove crackled its comfort to us, the kettle sang its song as we settled ourselves beside the stove with our feet in the oven until we were thoroughly warmed. Sometimes the mail included all the newspapers from Monday’s to Friday’s editions. Father sat in his usual place at the head of the table, arranged his papers in proper daily order, asked to have the lamp “shoved down this way,” and began to read the news which was already almost a week old. Toast was made, tea was brewed, and our chairs drawn up to the kitchen table; we buttered our toast and drank our tea, and thought of the two care-free days ahead of us when we could share all our cares, and worries, as well as our joys with “Dad” and “Mom”.

Monday morning came early during those winters. A stove pipe led up from the furnace in the cellar, through the dining room and into the bedroom my sister and I shared. At five o’clock a sharp knocking on the stove pipe in the dinning room wakened us and we knew that Father was up, had the fire on in the kitchen stove and was off to the stable to feed the horse. Mother was up next to make breakfast - porridge, toast and tea. By the time we were downstairs, Father was in from the stable and we all ate breakfast which was usually a silent meal; our thoughts were concerned with being on time for the train. However, we need not have worried, Father always had us at the station a good half hour early. Father then drew the cutter out of the shed, took up the lantern and went to the stable for the horse. As soon as we saw the lantern coming up, we picked up our grips and Father’s fur coat and went our into the cold and dark morning. After the horse was hitched to the cutter, we held Father’s coat for him, put out the lantern and set it inside the shed, wrapped ourselves in the robe and we were off up the lake to catch the seven O’clock train that would take us to the town of Lindsay for our week at school. The station was a small room with several windows, a bench along two walls, and wicket out of which the agent poked his head to sell us our tickets, and a round stove that did its best to warm us with a blazing fire. Father let us out of the cutter, gave us a loving look, turned his horse around, and headed for home just as the train got up full steam for the trip. Each Monday morning in the new year showed us a sun rising earlier and earlier until we realized that with the coming of spring we would soon have to give up travelling on the lake.

In the spring, as the sun became stronger, the lake would “water up during the day; at night the water would freeze and the next morning the skating would be great. One Monday morning Mother was doing the family washing - tubs, boiler, wash board, home made soft soap were in full swing when Father come in and mentioned how good the skating was. I shall never forget Mother drying her water - soaked hands, getting out her skates and going with me to the lake for an hour of skating. Wonderful childhood!

The big question in the spring was, “When will the ice go out this year? It went out in the middle of April last year.” The lake took on a gray and fearsome appearance; the river’s current spread into the lake; the ice along the shore gave way and the stage was set for the ice to go out. Some years a strong west wind would drive it pell-mell onto the shore where it wrecked a dock or tow just for the fun of it. Some years the sun would beat down day after day and even a good stiff breeze would carry the rotten ice down into the next lake and on the way it would be crushed or melted before it got very far. As soon as the ice had gone out, the land began to warm up and the lake had gone full circle again, and we were ready for spring. Big Island exchanged its gray tones for pale greens of various tones which grew stronger and deepened with each day until summer was well upon it.

The lake. At times we loved it for its caressing touch and its gentle swells and soothing sounds. At times we feared it for its tumult and its pounding when we strove to make our way across it to the shore. There were times when it took helpless fool-hardy people to its own depths. But to us, who respected its moods, it became a balm to our souls as we tried to sort out the “why’s and wherefore’s” of our lives.