What is the problem asking?

Molar mass of \(CuSO_{4}\) = g/mol = ?

Apply your Knowledge

Learn the theory at your own pace, try examples and test your new abilities with the quiz.

(Click the banner to open.)

Quantifying Chemical Compounds Theory

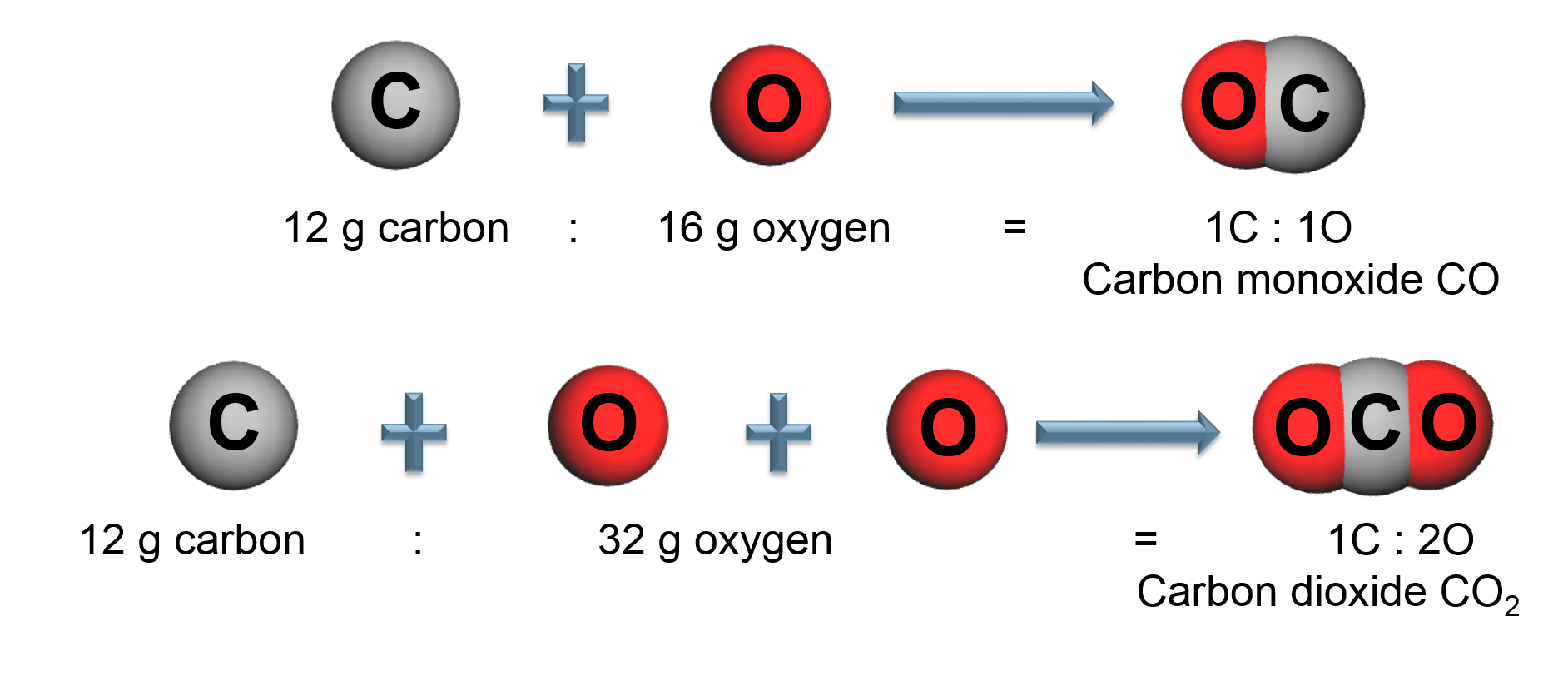

Elements combine in different ways to form substances whose mass ratios are small whole number multiples of each other.

All samples of a pure chemical substance always contain the same proportion of elements by mass regardless of their origin.

By mass, Carbon dioxide (\(CO_2\)) is: 73% Oxygen and 27% Carbon

All carbon dioxide is chemically the same in every location.

We know:

One mole is equal to \(6.022\)x\(10^{23}\) objects.

One mole of any element equals its molar mass.

1 mole of carbon (C) has a mass of: 12.01 g

Amedeo Avogadro - Inventor of the mole.

Molecules and the Mole:

One mole is equal to \(6.022\)x\(10^{23}\) objects.

One mole of any compound is equal to the sum of the molar masses of all elements in the compound.

1 mole of carbon dioxide \(CO_{2}\) a mass of : \(12.01\,g + 16.00\,g + 16.00\,g = 44.01\,g\)

Numbers of moles IS A DIRECT COMPARISON of the relative number of atoms or molecules!

The mole is used extensively in chemical problems because numbers of atoms can be compared!

Empirical Formula

The lowest whole integer numbers representing an atomic ratio of a molecule using a chemical description.

Empirical Formula of hydrogen peroxide: HO

Molecular Formula:

A chemical description of the actual complete molecule.

Molecular Formula of hydrogen peroxide: \(H_2O_2\)

NOTE

Some compounds have empirical and molecular formulas that are the same.

Empirical Formula of water: \(H_{2}O\)

Molecular Formula of water: \(H_{2}O\)

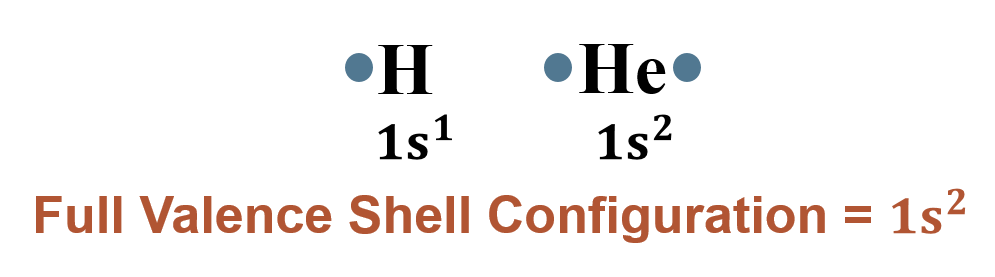

We know:

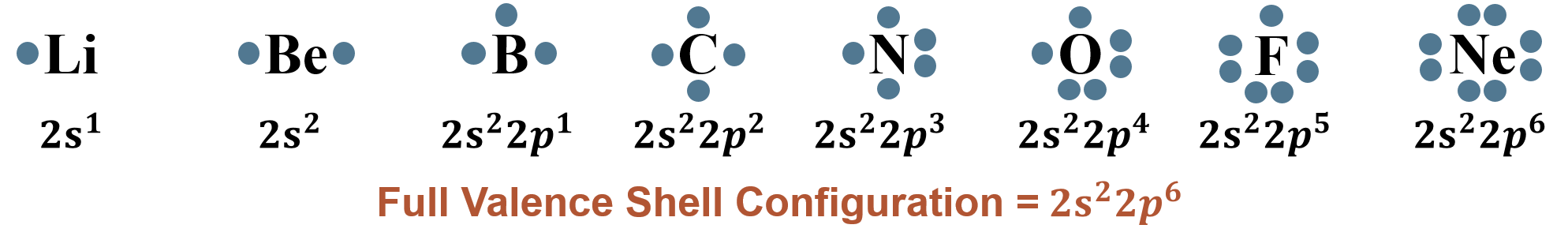

The periodic table is organized to help predict the properties of elements.

Elements down a column have similar chemical properties.

Periodic Trends:

The periodic table is organized to help us determine useful information about elements. For example: atomic radius, electronegativity, and ionization energy. Learning periodic trends can help us understand why certain elements have the properties we observe.

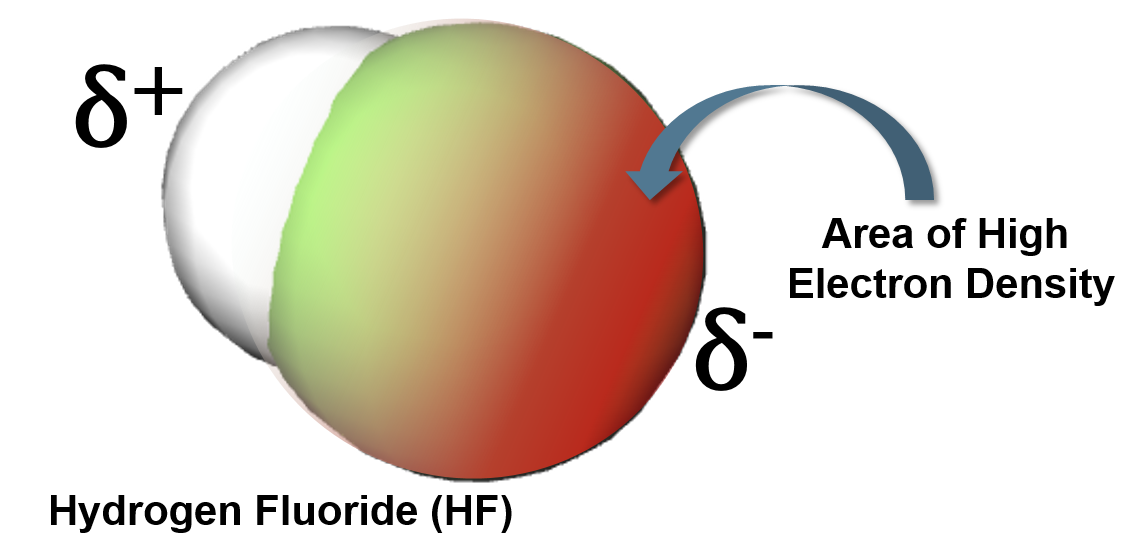

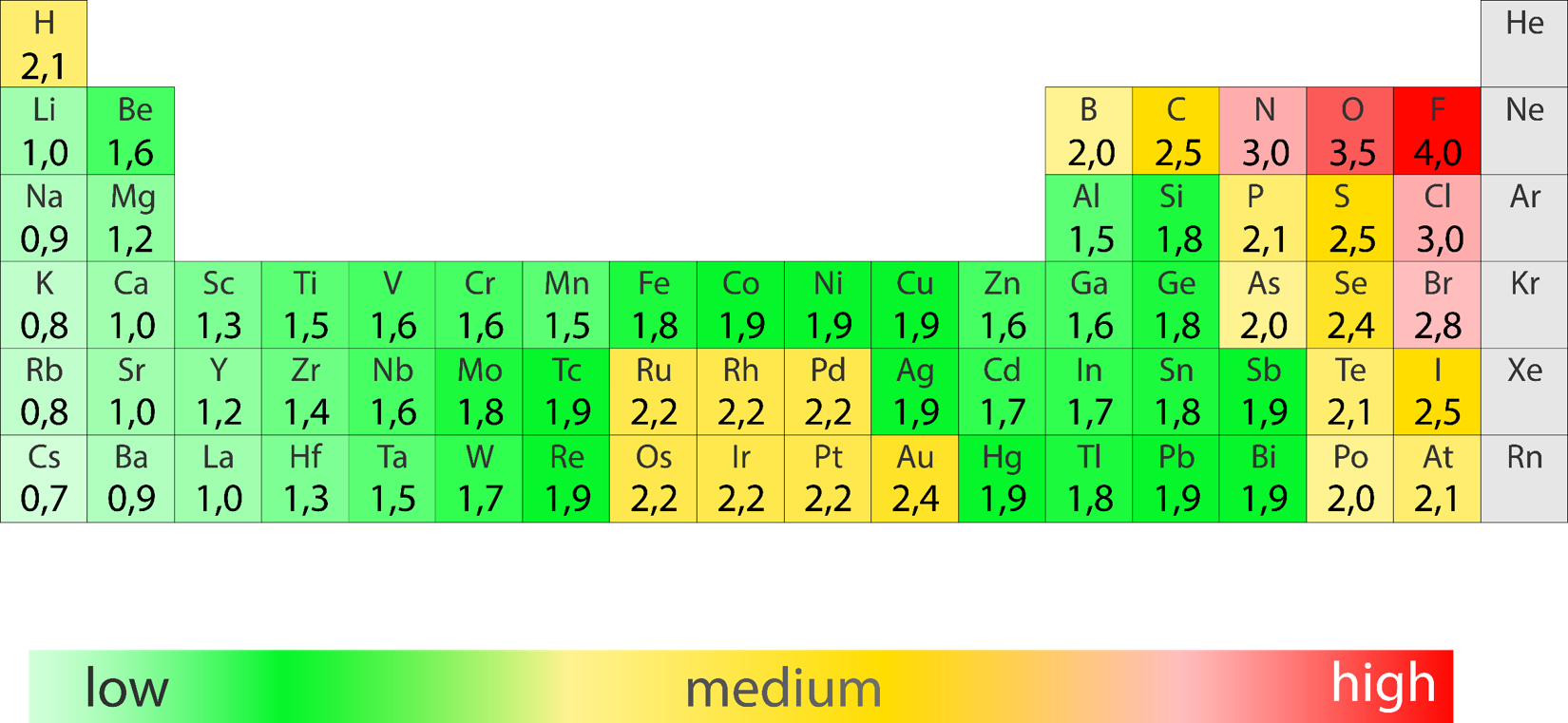

Electronegativity

The ability of a bonded atom to attract electrons

Moving down a column on the periodic table electronegativity decreases

Moving across a row on the periodic table electronegativity increases

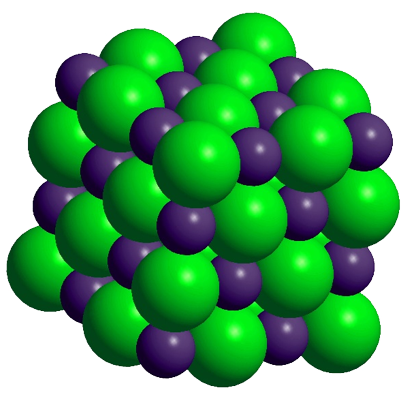

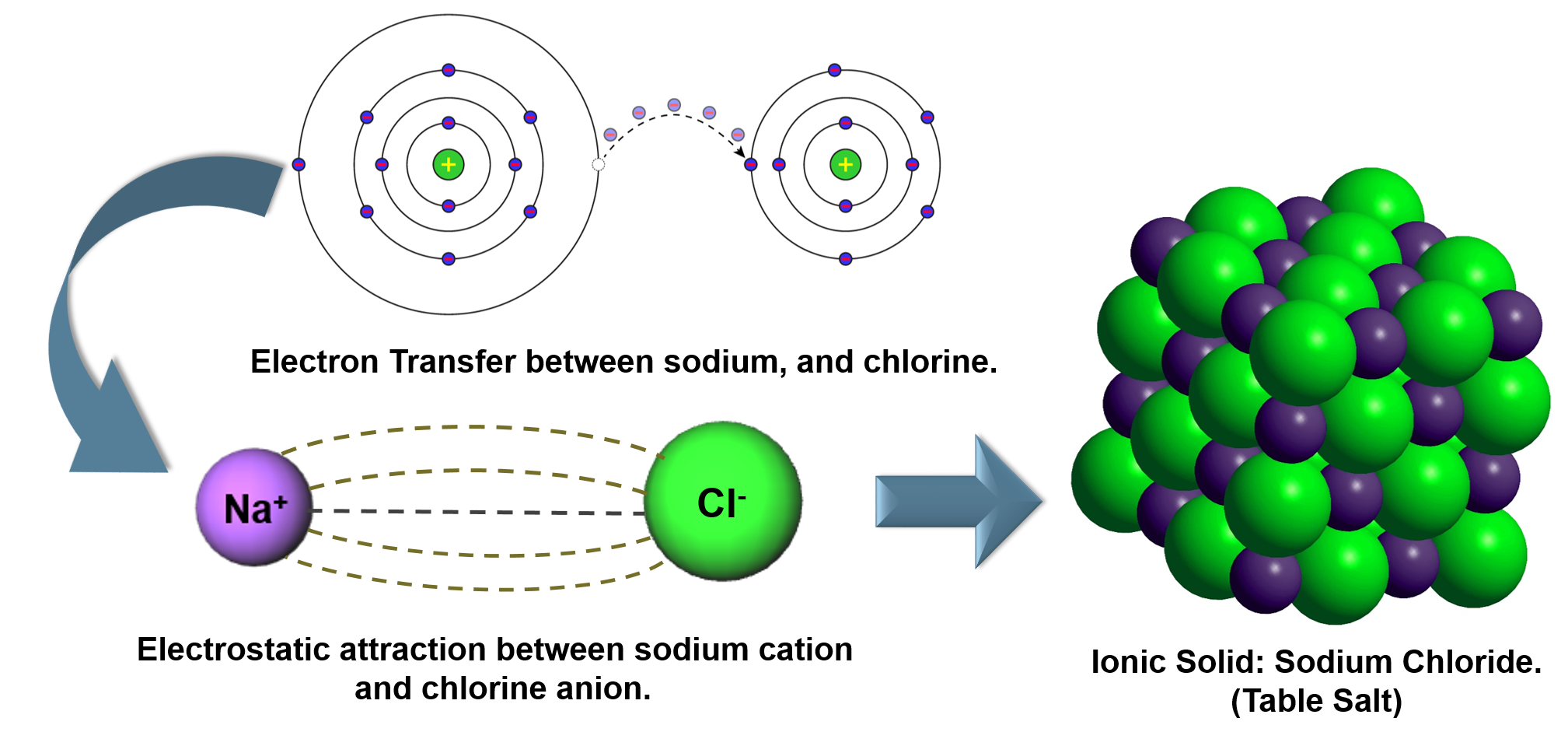

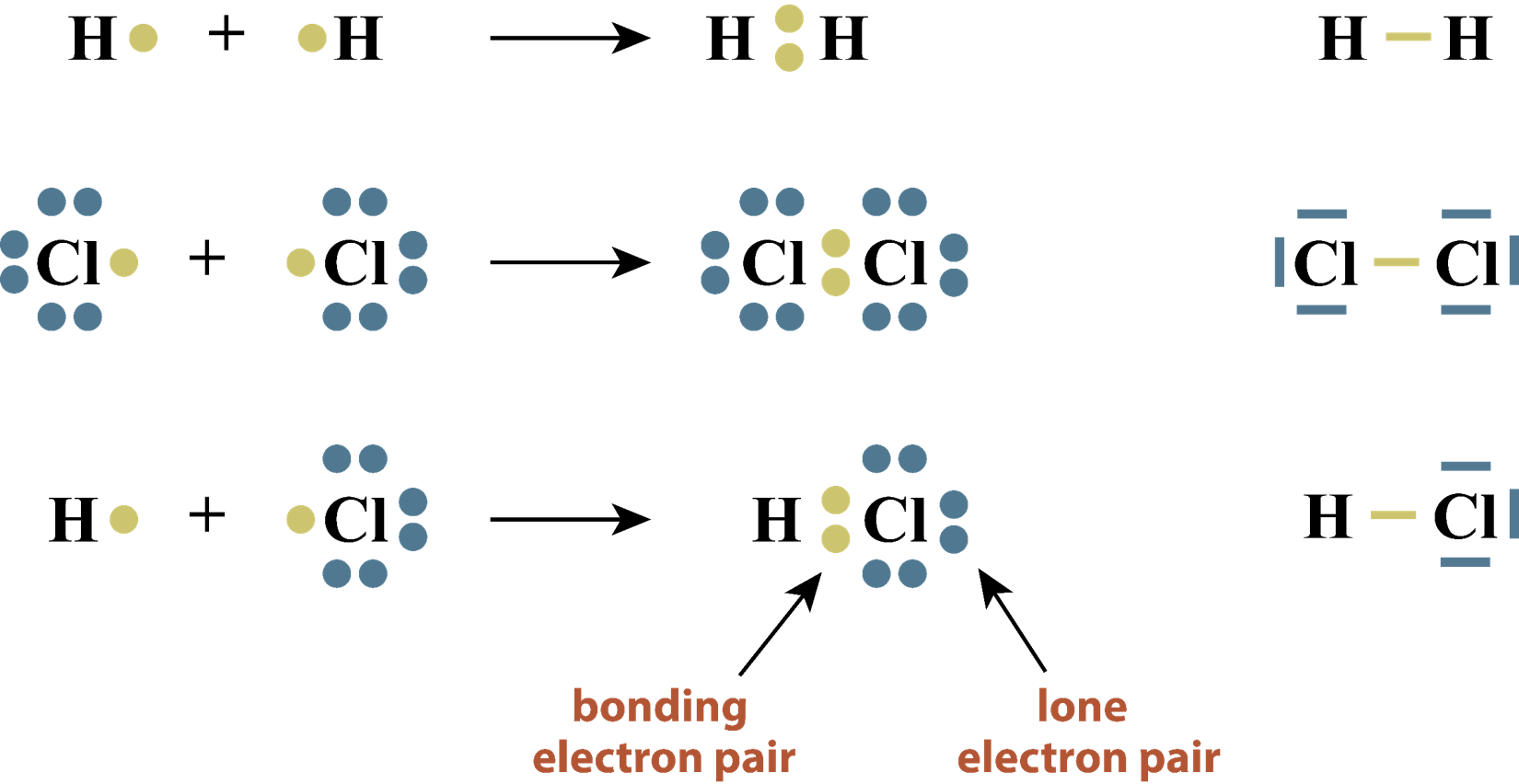

The difference in electronegativity determines bond type

Electronegativity differences (ΔEN) for bonded atoms can be calculated by subtracting the least electronegative atom from the atom with the highest electronegativity.

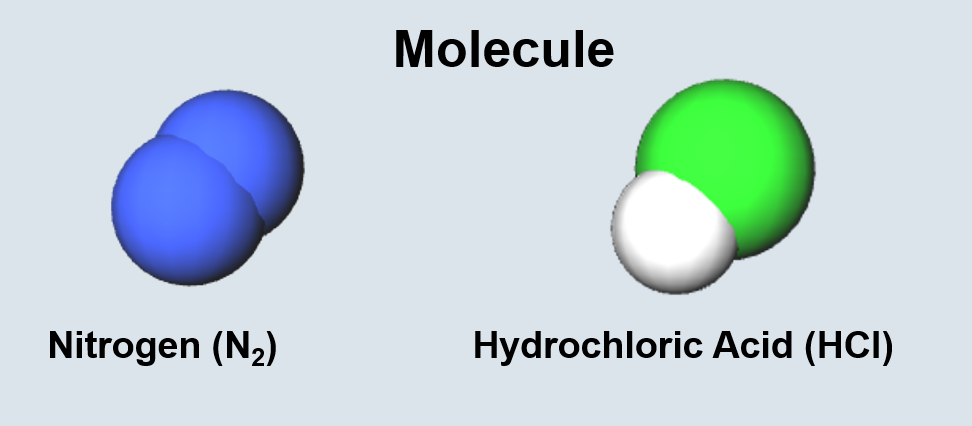

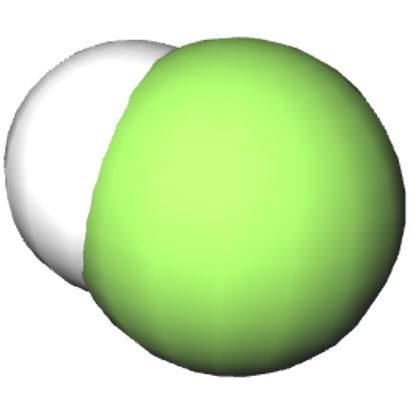

For hydrochloric acid (HCl):

Electronegativity of Cl=3.0

Electronegativity of H=2.1

∆𝐄𝐍=𝟑.𝟎-𝟐.𝟏=𝟎.𝟗

Is the bonding radius determined from averaging measurements of many compounds and molecules

The bond length of a two bonded atoms is determined by adding their bond radii

Moving down a column on the periodic table the principle quantum number (n) of the outermost electrons increases, orbitals are larger, therefore the atomic radii are larger.

Moving across a row the electrons in the outermost shell feel the charge from the nucleus more strongly. Electrons are closer to the nucleus, orbitals are smaller, therefore the radii are smaller

On the periodic table bond radius increases down a column.

On the periodic table bond radius decreases across a row.

Atomic Radius and Ions:

Cations have a smaller ionic radius than the neutral atom.

Anions have a larger ionic radius than the neutral atom.

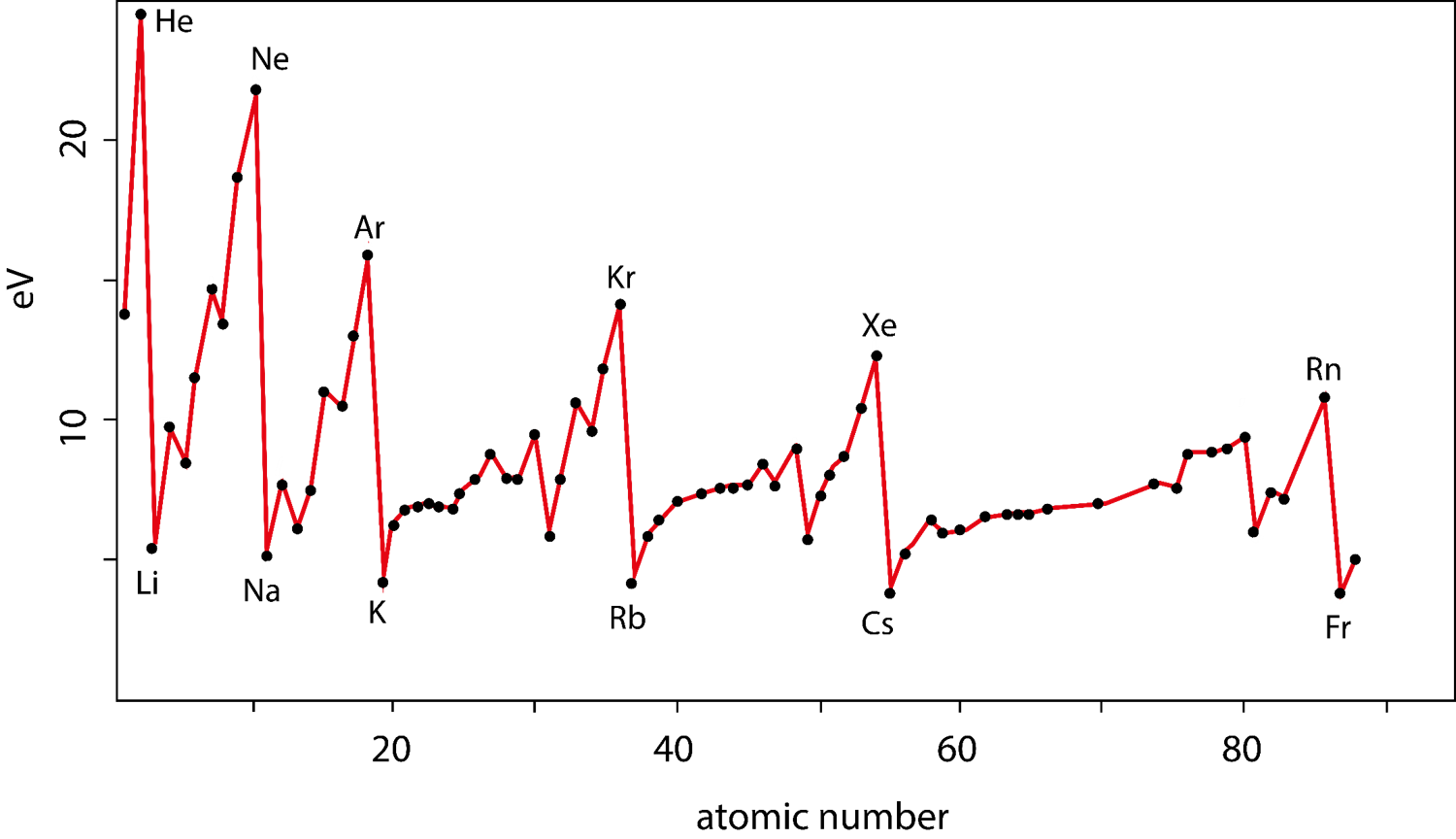

The amount of energy required to remove one electron from an atom (or ion) in a gaseous state.

Moving down a column on the periodic table the principle quantum number (n) of the outermost electrons increase, orbitals are larger, therefore it takes less energy to remove an electron because they are farther from the nucleus.

Moving across a row the electrons in the outermost shell feel the charge from the nucleus more strongly, orbitals are smaller, therefore it takes more energy to remove an electron because they are closer to the nucleus.

On the periodic table ionization energy decreases down a column.

On the periodic table ionization energy increases across a row.